The US And Europe Have Cut Billions In Health Aid — Can Anyone Fill The Gap?

uaetodaynews.com — The US and Europe have cut billions in health aid — can anyone fill the gap?

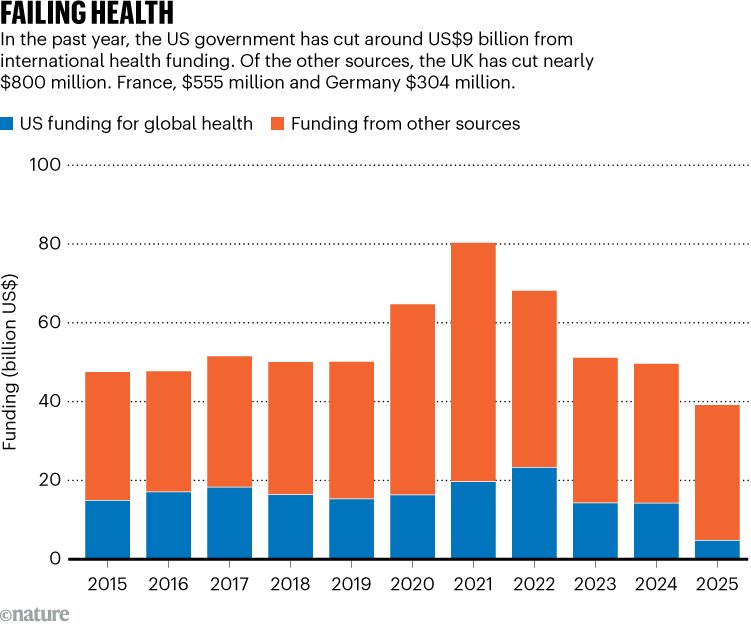

Who will pay for global health? Scientists and policy leaders explored this question when they met this week at the World Health Summit in Berlin. The reason: a steep and consistent fall, beginning in 2021, in international funding for health services in low- and middle-income countries (see ‘chart failing health’).

The United States has made the deepest cutsabout US$9 billion, after the start of the year, when the administration of US President Donald Trump slashed funding to the US Agency for International Development. One estimate found that, by 2030, these cuts could lead to 14 million deaths globally1. The United States has also pulled out of the World Health Organization (WHO), withdrawing funding that represented around one-fifth of the $6.7-billion programme budget in 2022–23.France, Germany and the United Kingdom are also scaling back, according to data published by the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluationbased at the University of Washington School of Medicine.

Source: IHME

“In Jordan, we lost lives immediately when health care in hospitals stopped abruptly,” says Haitham Bashier, director of the Public Health Emergency Management Centre in Amman. At the Eastern Mediterranean Public Health Network, a regional public-health organization in Jordan, “60% of our funding for health projects came from US-based funds. Now it’s gone,” Bashier told Nature at the summit.

However, Bashier also said the cuts are “a rare opportunity to reimagine how the global health ecosystem functions”. “We’ve been implementing an agenda imposed onto us by somebody else. We mustn’t repeat the old US-donor system,” he says.

Take control

Notwithstanding the cuts, this year, high-income countries spent nearly 300 times more on development assistance for health than low-income countries spent on their own health systems. The consensus among health leaders attending the summit is that these countries should now take control of their own health costs.

“The global south has failed in the last 25 years to finance our own primary health-care systems,” says Joy Phumaphi, executive secretary of African Leaders Malaria Alliance in Tanzania. “This was a serious act of negligence. But we have the capacity to reclaim this space and develop our own capabilities and institutions for our own health systems. We are beholden to make these government investments,” she adds.

John-Arne Røttingen, chief executive of Wellcome, the health-research charity in London, agrees it’s time for a rethink.“The fact is that countries have been establishing health care that follows the plans of external financing,” he says. “A country like Malawi has something like 50 different health plans all catering to different scopes of the international system.”

“In a partnership on equal footing, one side cannot decide to reduce a previously agreed contribution by 25% or 50%. (That’s why) a cooperation agreed between partners on equal footing should be more reliable than a donor–recipient relationship,” says Gorik Ooms, a health-policy researcher at the Institute of Tropical Medicine Antwerp in Belgium.

Who will fill the gaps?

One big question is where funding will come from to fill the gaps left by the United States and European countries, and whether new funders will bring new demands. Philanthropic donors such as Wellcome and the Gates Foundation, based in Seattle, Washington, are not filling gaps left by US and European governments.

In May, China committed $500 million to the WHO after the United States withdrew from the agency. However, some researchers don’t think that China will step up further. “Those are not gaps China has ever aspired to fill,” says Karen Grépin, a health-policy researcher at the University of Hong Kong.

China’s strategy is different from that of Western donors, Grépin says. “It’s more likely to provide aid linked to infrastructure investments,” she adds. But as other donors scale back, “I do see China becoming an even more influential partner to countries around the world in terms of global health.”

What next for WHO?

Delegates at the summit also discussed the future role of the WHO as it restructures following US funding cuts. One proposal was that the WHO could facilitate health-care programmes but leave more of the health-care delivery to national governments. Along with other international organizations, it could also coordinate research and development (R&D), health data sharing and creation of new technologies like digital health and artificial intelligence. Røttingen told Nature this might mean that “funders now need to relinquish some of their powers to national governments and align with their national plans and priorities”.

Røttingen adds that international organizations can do better to support global collaboration in the logistics of rolling out new health technologies. “The major improvements in child health and life expectancies have been driven by new technologies and their scale up. In a world with fewer resources, we need to get more efficient at delivering those potentials.”

Disclaimer: This news article has been republished exactly as it appeared on its original source, without any modification.

We do not take any responsibility for its content, which remains solely the responsibility of the original publisher.

Disclaimer: This news article has been republished exactly as it appeared on its original source, without any modification.

We do not take any responsibility for its content, which remains solely the responsibility of the original publisher.

Author: uaetodaynews

Published on: 2025-10-16 18:15:00

Source: uaetodaynews.com